- Home » News » World News

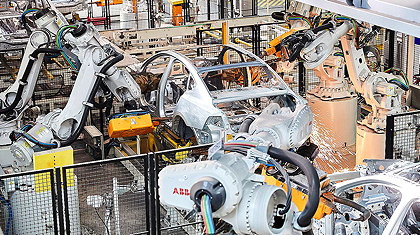

US researchers find that every robot replaces 3.3 jobs

American researchers have calculated that every new industrial robot installed in the US between 1993 and 2007 replaced 3.3 jobs. But in a separate analysis of French industry from 2010 to 2015, they have also found that firms that adopt robots quickly became more productive and hire more workers, while their competitors fall behind and shed workers – with jobs again being reduced overall.

The results have been published in a series of three papers written by Professor Daron Acemoglu, an economist at MIT, with several co-authors. In one of the papers, Acemoglu and Dr Pascual Restrepo, an assistant professor of economics at Boston University, conclude that from 1990 to 2007, each additional robot in US manufacturing replaced about 3.3 workers and also lowered wages by around 0.4%, with some parts of the US affected more than others.

They say that while claims about machines wiping out human work entirely may be overstated, the robot effect is “a very real one in manufacturing with significant social implications”.

The findings “certainly won’t give any support to those who think robots are going to take all of our jobs,” Acemoglu states, “but it does imply that automation in a real force to be grappled with”.

In the second study, co-authored by Acemoglu, Restrepo and Clair Lelarge, a senior research economist at the Banque de France and the Centre for Economic Policy Research, the researchers looked at 55,390 French manufacturers, of which 598 bought robots between 2010 and 2015. They found that these robot users became more productive and profitable, while the share of their income going to their workers fell by 4–6%. However, because their investments in technology fuelled growth and boosted their market shares, they added more workers overall.

By contrast, firms that did not add robots saw no change in their labour share, and for every 10% increase in robot adoption by their competitors, their own employment fell by 2.5%. Essentially, the firms not investing in technology lost ground to their rivals.

“Looking at the result,” Acemoglu comments, “you might think [at first] it’s the opposite of the US result, where the robot adoption goes hand-in-hand with destruction of jobs, whereas in France, robot-adopting firms are expanding their employment. But that’s only because they’re expanding at the expense of their competitors. What we show is that when we add the indirect effect on those competitors, the overall effect is negative and comparable to what we find the in the US.”

“In France, it’s only the firms that adopt robots – and they are very large firms – that are reducing their labour share, and that’s what accounts for the entirety of the decline in the labour share in French manufacturing,” Acemoglu adds.

In his third paper (again co-authored with Dr Restrepo), Acemoglu argues that automation has a bigger impact on the labour market and income inequality than previous research has suggested, and identifies 1987 as the year when jobs lost to automation stopped being replaced by an equal number of other workplace opportunities.

Before 1987, industries that adopted automation lost 17% of their jobs, but also created 19% more new job opportunities. After 1987, the losses stayed at 16%, but the new job opportunities fell to 10%.

“A lot of the new job opportunities that technology brought from the 1960s to the 1980s benefitted low-skill workers,” Acemoglu reports. “But from the 1980s – and especially in the 1990s and 2000s – there’s a double-whammy for low-skill workers. They’re hurt by displacement [job losses], and the new tasks that are coming, are coming slower and benefitting high-skill workers.

“Productivity growth has been lacklustre,” he adds, “and real wages have fallen. Automation accounts for both of those. Demand for skills has gone down almost exclusively in industries that have seen a lot of automation.”

Acemoglu sees automation as a special case within a larger set of technological changes in the workplace, “because it can replace jobs without adding much productivity to the economy”.

“It’s not all doom and gloom,” he adds. “There is nothing that says technology is all bad for workers. It is the choice we make about the direction to develop technology that is critical.”

The International Federation of Robotics (IFR) has reacted to Acemoglu’s findings, pointing out that during the period 2013–2018, when the global stock of industrial robots grew by 65%, the number of people working automotive industry – the biggest user of robots – in the US grew by 22% from 824,400 to 1,005,000. The IFR adds that robot adoption will likely be a critical determinant of productivity growth for the post-Covid-19 global economy.

The IFR also cites OECD research that shows that companies that use technology effectively are ten times more productive than those that do not.

“The impact of automation on employment is not in any respect different from previous waves of technology-driven change,” comments IFR president, Milton Guerry. “Productivity increases and competitive advantages of automation don’t replace jobs – they will automate tasks, augment jobs and create new ones.”

The IFR adds that companies around the globe are reassessing their global supply chain models in reaction to the lessons learned from Coronavirus. “This will likely accelerate the introduction of robots, leading to a renaissance of industrial production in some regions – and bringing back jobs,” it suggests. After the crisis, IFR expects a considerable boost for robotics and automation, even if the industry cannot currently decouple itself from the economic downturn.

• Professor Daron Acemoglu and his co-researchers have published their findings in three papers: Competing with Robots: Firm-Level Evidence from France and Unpacking Skill Bias: Automation and New Tasks, both published in American Economic Association: Papers and Proceedings; and Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets published in the Journal of Political Economy.